Debt Ceiling Deal Curtails GOP-Backed Budget Cuts, Spending Caps

The deal will freeze non-military discretionary spending this year and allow a 1 percent increase in 2024.

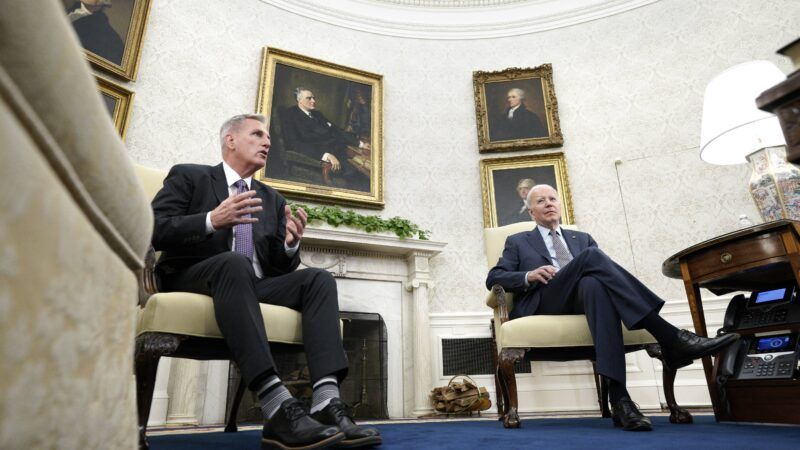

After a monthslong standoff, President Joe Biden and Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy (R–Calif.) announced a deal to raise the federal government's debt limit and avert the first default in U.S. history.

The deal will suspend the debt limit through January 2025—in other words, until after the winners of the next presidential and congressional elections are sworn-in—and caps non-military discretionary spending for each of the next two years. According to multiple media reports, the caps will hold steady that part of the federal budget at 2023 levels next year and will allow for a 1 percent increase in 2025. After that, the caps will be removed.

The agreement also reportedly includes some Republican demands, like increased work requirements for food stamp recipients, clawing back some unspent COVID emergency funds, and rescinding some of the $80 billion in new funding given to the IRS in last year's budget resolution. The specifics will become more clear later on Sunday, when the text of the bill is scheduled to be released.

For now, as expected, both sides are claiming victory. "GOP leaders [are] claiming they got big cuts to domestic programs," tweeted Washington Post economics reporter Jeff Stein on Sunday morning. Meanwhile, Democrats are "claiming it's essentially a funding freeze (conservatives agree)," he added.

Between those diverging views of the deal, it would appear that the Democrats and conservative Republicans are closer to telling the truth. Indeed, the House GOP effort to reduce federal spending as part of the debt ceiling deal seems to have ended up on the cutting room floor.

Recall that, last month, McCarthy successfully stewarded a bill—The Limit, Save, Grow Act—through the House last month that would have actually cut federal spending and raised the debt ceiling. That package would reset the federal budget baseline to where it was last year—that is, before the December passage of the $1.7 trillion omnibus bill that jacked up spending across the board—would limit future budget growth to one percent annually for the next decade, and would slow the accumulation of future debt.

In other words, it included a more sizable spending cut and a longer period of future spending restraint than the deal struck this weekend.

Of course, it was always unlikely that Republicans could get that bill through the Senate and get Biden to sign it. Even so, the gap between those goals and the newly announced debt ceiling deal is remarkable—and not in a way that looks particularly impressive for McCarthy.

"The big GOP win here is that they forced Biden to agree to flat nominal discretionary spending for one year and then a one percent nominal increase the year after that, which is a significant cut in inflation-adjusted, per capita, or GDP terms," notes liberal pundit Matt Yglesias on his Slow Boring substack. "But that's something Republicans could (and would) have gotten through the normal appropriations process anyway."

Yglesias' post is aimed at showing Democrats and liberals that Biden made a good deal, but his point also highlights how Republicans fell short here. Since the House controls much of the budget-making process, McCarthy could have effectively imposed a spending freeze or 1 percent discretionary spending growth over the next two years simply by passing budgets that did exactly that. If Biden (or the Senate) refused to go along, the House could respond by passing continuing resolutions that hold spending to current levels. "The point of debt ceiling hostage-taking was supposed to be to win spending concessions that can't be won through the normal appropriations process," Yglesias writes.

He's exactly right. But McCarthy took Social Security and Medicare (the real drivers of unsustainable future debt) off the table early on during negotiations. Now, by abandoning the attempt to cut spending back to last year's levels, the deal effectively cements the new, higher federal baseline established by December's omnibus bill. That's a obvious victory for Biden and the Democrats.

And what did McCarthy get in return? Some minor changes to work requirements for food stamp recipients, which will allow Republicans to posture about being tough on welfare but which won't meaningfully reduce future deficits. Trimming some of the new IRS funding and rescinding unspent COVID funds are fiscally responsible policies, for sure, but they are also things that could have been accomplished through other means.

Everything the Republicans won in this negotiation is "stuff they could have just as easily gotten in a vanilla budget fight or Farm Bill reauthorization," concludes Semafor editor Jordan Weissmann.

McCarthy may now have a hard time selling this deal to his own members. Rep. Ralph Norman (R–S.C.) called the deal "insanity" in a Saturday night tweet. "A $4 [trillion] debt ceiling increase with virtually no cuts is not what we agreed to," Norman wrote on Twitter. "Not gonna vote to bankrupt our country. The American people deserve better."

Let's be clear: the most important part of any deal to raise the debt ceiling and avoid defaulting on the national debt is…avoiding defaulting on the national debt. This agreement checks that essential box.

But the debate over the debt ceiling has long been a proxy for a broader debate over the trajectory of federal spending—and it is one of the few effective mechanisms for putting real restraints on future spending. If the goal was merely to raise the debt ceiling without seriously reducing future federal spending, McCarthy could have ended this showdown months ago.

Instead, he pushed to the brink, risked an economically disastrous default, and seemingly came away with little to show for it.

Show Comments (158)