Prohibition Gave Us Tranq-Laced Fentanyl

Mixing other drugs with xylazine is driven by the economics of prohibition.

The emergence of the animal tranquilizer xylazine as a fentanyl adulterant has prompted law enforcement officials to agitate for new legal restrictions and criminal penalties. That response is fundamentally misguided, because the threat it aims to address is a familiar consequence of prohibition, which creates a black market in which drug composition is highly variable and unpredictable.

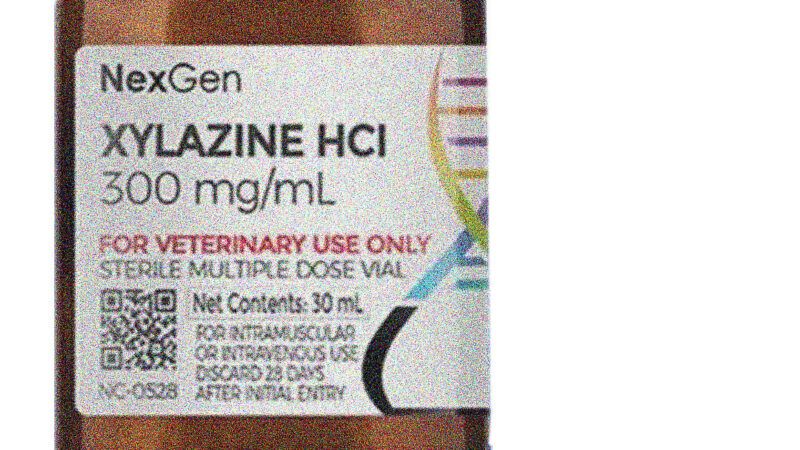

Xylazine, a.k.a. "tranq," was first identified as a drug adulterant in 2006, and today it is especially common in Puerto Rico, Philadelphia, Maryland, and Connecticut. The combination of fentanyl and xylazine poses special hazards.

Like opioids, xylazine depresses respiration, so mixing it with fentanyl can increase the risk of a fatal reaction. Unlike a fentanyl overdose, a xylazine overdose cannot be reversed by the opioid antagonist naloxone.

Xylazine also seems to increase the risk of serious and persistent skin infections and ulcers, which have always been a hazard of unsanitary injection practices. According to a 2022 article in Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries, "the presumed mechanism" is "the direct vasoconstricting effect on local blood vessels and resultant decreased skin perfusion," which impairs healing.

In 2022, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reports, xylazine was detected in 23 percent of fentanyl powder and 7 percent of fentanyl pills analyzed by its laboratories. But before the DEA was warning us about xylazine in fentanyl, it was warning us about fentanyl in heroin, and both hazards are the result of laws that the DEA is dedicated to enforcing.

From the perspective of drug traffickers, fentanyl has several advantages over heroin. It is much more potent, which makes it easier to smuggle, and it can be produced much more cheaply and inconspicuously, since it does not require opium poppies. Xylazine has similar advantages: It is an inexpensive synthetic drug that can be produced without crops. And unlike fentanyl, it is not classified as a controlled substance, which makes it easier to obtain.

American drug users are not clamoring for xylazine in their fentanyl, any more than they were demanding fentanyl instead of heroin. The use of such adulterants is driven by the economics of prohibition. And as usual with illegal drugs, consumers do not know what they are getting. Whether it is vitamin E acetate in black market THC vapes, MDMA mixed with butylone, levamisole in cocaine, or fentanyl pressed into ersatz pain pills, prohibition reliably makes drug use more dangerous.

Much to the dismay of veterinarians, drug warriors alarmed by tranq have proposed treating xylazine as a controlled substance. As usual, they think the solution to a problem created by prohibition is more prohibition.

Show Comments (42)