Biden's Student Loan Plan Could Cost Twice as Much as Projected

Unlike the Education Department's estimates, a CBO analysis considers how the new rules will encourage more students to take out loans they won't be able to pay back.

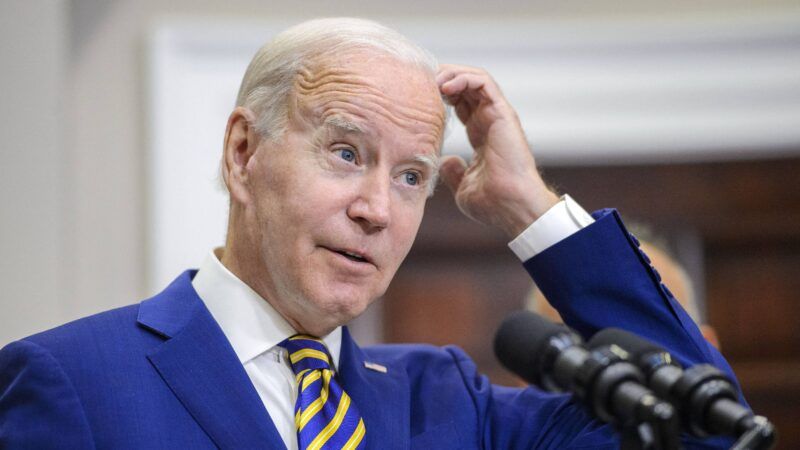

Regardless of how the U.S. Supreme Court rules on President Joe Biden's plan to forgive up to $20,000 in student loan debt for some federal borrowers, the White House is also pushing ahead with a new repayment plan that will lower what many student borrowers end up owing.

It's going to be significantly costlier than the Department of Education originally projected.

A new analysis from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) shows that Biden's so-called income-driven repayment plan will cost at least $230 billion over 10 years—with an additional $45 billion in costs likely coming if the Supreme Court invalidates the White House's student loan forgiveness scheme. That means the final tab could be more than twice the $138 billion price tag attached to the proposal by the Department of Education, which is overseeing the program's rollout.

Under current law, federal student loan payments are capped at 10 percent of an individual's "discretionary income," which the Department of Education defines as income that exceeds 150 percent of the federal poverty guidelines. In practice, that means a single borrower with no children starts making payments on income that exceeds $20,400.

Biden wants to lower that threshold to 5 percent for undergraduate loans and impose a new limit of 10 percent for loans put toward a graduate degree. Biden's plan would also wipe away outstanding student debt after 10 years of payments for those who borrowed $12,000 or less—and a maximum payment period of 20 years no matter how much was borrowed.

But if you cap monthly payments at a lower level and also shorten the allowable repayment time, there will be a lot of loans that never get paid back in full. That cost ultimately falls on the taxpayers, and that's what the dueling estimates from the CBO and the Department of Education are all about.

The gap between the two estimates is a telling one.

The CBO points out that the Department of Education did not account for the "behavioral effects" of the new policy—in other words, it did not include estimates for how many additional students would take out loans if the repayment method was altered.

The CBO, however, did. It found that reducing what student loan borrowers will eventually have to pay back unsurprisingly caused more students to take out loans—including loans that they would be unable to pay off in full. Overall, the annual volume of student loans would increase by about 12 percent, the CBO estimated, with both undergraduate and graduate students seeking more loans.

"Students who would be expected to take out federal loans would borrow more," Leah Koestner, a CBO budget analyst concluded in a presentation on Wednesday. And "some students who would not be expected to borrow under current law would take out loans."

Biden would be continuing a now-decadeslong trend of reducing the limits on the federal government's income-driven repayment plans for student loans—and an equally long trend of those changes costing more than the Department of Education anticipates.

It was President George W. Bush who signed into law the first income-driven repayment plan. As Reason's Mike Riggs explained in the November 2022 issue, the original plan "pegged monthly loan payments for participating borrowers to 15 percent of their adjusted gross income and forgave the remaining balance of those loans after 25 years. In 2015, Obama shortened those numbers to 10 percent and 20 years for many borrowers."

"All of these policies," Riggs wrote, "have costs that eclipsed the Education Department's projections, and that is because the Education Department sucks at projecting costs."

The CBO's projections of the long-term costs of Biden's payment plan could be wrong, of course, as all such estimates can. But to completely ignore the ways in which easing student loan payments might cause more students to take out more loans—as the Department of Education's model does—seems wildly flawed and obviously inaccurate.

The Biden administration says student loans are a debilitating cost on recent college grads, but this repayment policy will result in more students taking on more college debt—and passing the excess costs onto taxpayers. That hardly seems like a solution.

Show Comments (55)