5 Years After the Backpage Shutdown, Sex Workers—and Free Speech—Are Still Suffering

As former Backpage execs await their August trial, the shutdown is still worsening the lives it was supposed to improve.

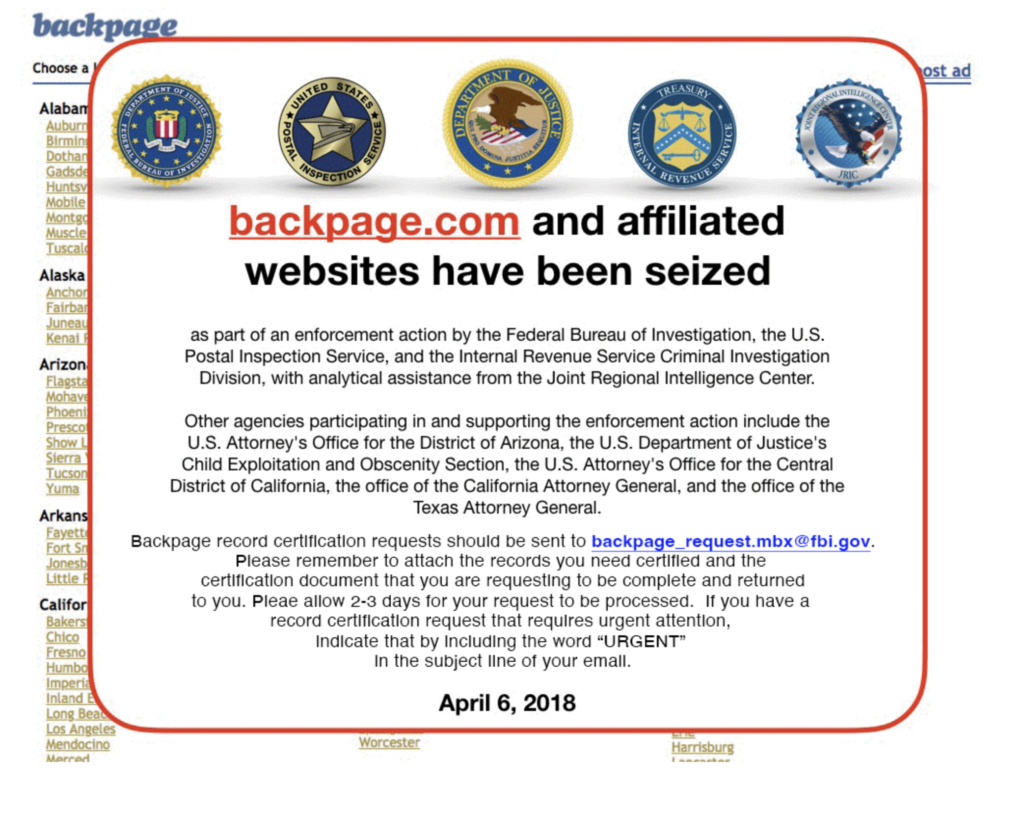

On April 6, 2018, the federal government seized and shut down the classified advertising platform Backpage, alleging that a group of current and former executives had used the website to facilitate prostitution. Five years later, two of these executives and a number of former users of Backpage reflect on what the prosecution and the platform's closure have meant.

The seizure of Backpage helped "activate" Kaytlin Bailey toward sex worker advocacy. "To know so many people who used this service to keep themselves safe, to schedule and screen their clients, and to have the government narrative be that these, like, evil sex traffickers are kidnapping and shipping children…has been absolutely bananas," says Bailey, a comedian, former sex worker, and the founder and executive director of the nonprofit Old Pros. "The fact that we have really really smart people who have fallen for this idea that we can end child sexual exploitation by removing websites on the internet—it continues to blow my mind."

Thinking about Backpage's shutdown fills sex worker advocate Phoenix Calida with "anger and sadness." It was "not only a place to advertise. It was a place to find community, learn, and find safety," says Calida. "If I didn't have Backpage to advertise or screen, I probably would be dead by now."

"While the effects of the demolition of Backpage were awful for sex workers, I think the most devastating effects are those which will proceed from the terrible precedents the persecution set," says sex worker and author Maggie McNeill. "By wantonly destroying an internet business which had not only broken no laws, but which had also prevailed time and again against predatory lawsuits based in a rather bizarre legal theory of vicarious liability, the government has demonstrated that it cannot and will not be constrained by Section 230, the First Amendment, or even the venerable principle of presumption of innocence."

Backpage co-founder James Larkin says the past five years have taught him that "if the government decides to point its finger at you, there's really no question that they're going to try to ruin you"—and that "given the system and the way it's set up," chances are high that it'll succeed.

How Backpage Was Seized

Shuttering Backpage was the main reason advocates and lawmakers cited for passing the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, or FOSTA. That law was signed into law by former President Donald Trump on April 11, 2018. That's just after the Backpage seizure and the arrest of some of its current and former staff—laying waste to claims that without a new law, the platform was untouchable.

Federal agencies went after Backpage using a much older law: the Travel Act. This 1961 law criminalizes traveling or using "the mail or any facility in interstate or foreign commerce" with the intent to "further any unlawful activity."

Prosecutors have been keen to give the impression that the "unlawful activity" in this case is child sex trafficking—so keen, in fact, that they triggered a mistrial with references to it when the case first went to trial in 2021. But the Backpage staff on trial are not accused of facilitating sex trafficking (that is, commercial sexual activity involving force, fraud, coercion, or minors). Rather, they are charged with violating state laws prohibiting plain old prostitution—the consensual exchange of sexual activity for money between adults.

Prostitution isn't a federal crime, but the Travel Act lets the Department of Justice (DOJ) intervene in cases involving alleged violations of some state-level crimes, including prostitution.

Backpage banned explicit ads for prostitution or any other illegal activity. But as a massive user-generated classifieds platform—where an enormous number of ads were posted daily for everything from used cars to nude modeling gigs—it was impossible to guarantee that ads for illegal services never got through (an issue far from unique to Backpage).

Backpage did allow ads for escorts, dominatrixes, strippers, and other forms of legal erotic services and adult entertainment. In practice, this allowed full-service sex workers —that is, folks engaging in prostitution—to advertise so long as they weren't totally open about their offerings (also a situation common across many online platforms).

These legal sex-work ads are, unambiguously, speech protected by the First Amendment—as former Backpage executives and newspaper publishers Larkin and Michael Lacey have argued all along.

"To me the issue is and always has been the speech," Lacey told Reason in March. "We platformed legal speech. The government didn't like the speech, but it was legal."

At the 2021 trial, the prosecution's lead law enforcement witness admitted that he couldn't say for certain whether any of the ads he claimed facilitated prostitution had actually led to the exchange of sex for money. If ultimately they did, it was beyond the knowledge or control of anyone at Backpage.

But that hasn't stopped the feds from an intense, protracted prosecution of Backpage executives—one in which numerous moves suggest they're not willing to fight fair.

For instance, prosecutors successfully fought to exclude exculpatory evidence that was sent to the defendants' lawyers by accident (and later published by Reason). They seized defendants' properties and their bank accounts, including assets unconnected to Backpage and funds arguably derived from protected speech.

The asset forfeiture happened "without a hint of due process," Larkin says. "Now for five years we have been unable to get a hearing on the monies they have frozen. That includes properties and assets that were purchased before backpage.com was even launched in 2004. That includes monies we paid lawyers and set aside for our defense."

"They're going to litigate us until we're dry as beef jerky," says Lacey, noting that a couple of the defendants "have now had to get federal public defenders because they have run out of money."

A new trial has been set for August 8, 2023—about five years and four months after Backpage was seized.

From Newspaper Moguls to Grocery-Store Pariahs

Lacey and Larkin started as publishers of alternative newspapers, beginning with the Phoenix New Times in 1970 and eventually encompassing papers in 18 cities, including the iconic Village Voice. In a pre-internet era, these publications were funded largely by print advertising, including a robust classified-ad business. Then came Craigslist, with a free-ad platform that upended their (and many other newspapers') funding models. To compete, they launched Backpage in 2004.

Originally, it focused on cities where Lacey and Larkin owned papers. It would eventually spread to areas around the U.S. and then around the world.

And, along the way, it would pick up a lot of powerful enemies.

After activists, attorneys general, and lawmakers pressured Craigslist to remove its "erotic services" section they turned their attention to Backpage, pressuring it, too, to stop allowing "adult" ads. But Lacey and Larkin resolutely refused. No strangers to fighting First Amendment battles against the government, they viewed adult ads not just as a moneymaker but as a matter of principle, too.

This commitment to free speech earned the pair and their colleagues an onslaught of legal troubles, including a failed 2016 attempt by then–Attorney General of California Kamala Harris to convict them of pimping.

Meanwhile, federal prosecutors tried—and failed—for years to find evidence that Backpage leaders were knowingly permitting sex trafficking. Instead, they found them cooperative with law enforcement and agencies like the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. A massive investigation in the early 2010s failed "to uncover compelling evidence of criminal intent or a pattern or reckless conduct regarding minors." Prosecutors concluded that "Backpage genuinely wanted to get child prostitution off of its site."

The prosecutors likewise found little to support a theory that Backpage executives knowingly allowed adult prostitution ads, admitting that even sexually suggestive posts could be for legal services. "While someone who has little experience with the adult services market may readily conclude that Backpage's escort advertisements offer prostitution services, such a conclusion is not so plain after one recognizes how much sexually explicit commercial conduct is lawful," they wrote in an internal memo.

If a prosecution must be brought, the best method would be to focus on Backpage not "as a co-venturer with pimps, but as a launderer of funds derived from adult prostitution," the prosecutors added back then.

This is the tack the DOJ eventually embraced. It charged Lacey, Larkin, and several others with multiple counts of violating the Travel Act, citing as evidence 50 ads published to Backpage between 2013 and 2018. In addition, some of the defendants faced money laundering charges and/or a conspiracy charge, for activities related to the publishing of or profiting off of ads that allegedly facilitated prostitution.

On the morning of April 6, 2018, the feds raided Lacey's home at gunpoint, storming his elderly mother in the shower, ransacking the house, and confiscating everything from computers to artwork to his wife's jewelry. Lacey and Larkin were arrested, jailed, and later released on bail set at $1 million each.

For the past five years, they have been required to wear location-tracking ankle monitors and unable to leave Maricopa County, Arizona, without permission.

The past five years have been brutal in many ways, Lacey and Larkin tell Reason.

Lacey likens living it to living with a perpetual rain cloud over his head. He notes that they've been dealing with prosecution in one way or another for more than five years, if you count the Harris charges in California. "It's seven years of having a really ugly finger pointed at you.…You can't work out enough to clear your head of the goblins that have taken up residence."

All of this has taken a toll on family members too, says Lacey. For instance, "I have a boy going off to graduate school and he's got a big scholarship but not a total scholarship, and I can't help him."

And then there are the day-to-day indignities of life with a court-ordered ankle monitor. Lacey says he was at a Safeway grocery store recently when it started beeping loudly at him that it needed to be charged. "Mothers and children are looking around as they're pushing their carts," he says. "It's insulting."

"I'm backed into a corner, and pretty much impoverished," adds Larkin. "But what else can I do? I'm going to continue fighting, because I know that we're innocent and this has been a political prosecution from day one."

'Everything Became So Much More Dangerous'

The impact of Backpage's shutdown extends way beyond Lacey, Larkin, and their co-defendants. For the untold number of workers who relied on Backpage to find customers, it's left a void that's been difficult to fill, especially in a post-FOSTA world.

Backpage "was always the best reliable way to connect with the most potential clients," says Ava Sinclaire, who describes herself as a porn star and a professional legal courtesan at Sheri's Ranch. Sinclaire credits Backpage with helping her leave behind a tough past and says for that she'll always be grateful. Despite "health issues that make it nearly impossible to hold down a 9/5, I've never been on disability or gotten money from the government," she says. "Backpage allowed me to be self-sufficient."

The loss of Backpage was especially hard for rural or remote sex workers, says filmmaker and dominatrix Bella Vendetta. Backpage "was one of the few places you could advertise for smaller, rural communities." Without it, sex workers in rural communities have nowhere to reach customers and nowhere "to connect with other workers or vet clients. Everything became so much more dangerous."

That the government's actions have made things more dangerous is a complaint heard again and again from sex workers. Neither FOSTA nor the takedown of Backpage and other platforms (the feds went after a number of them, starting with MyRedBook in 2014) has stopped people from engaging in sex work so much as made their lives and work less safe.

Backpage's shutdown "completely destroyed my chances of working safely in every way possible, and my money flow," says Delta Asher Hill, author of Sexual Liberty: Memoirs of a Sex Worker's Fight for Freedom. "It's harder to vet clients, many of my friends resorted to working on the street again, and cops still think consenting workers are victims."

Online platforms allowed sex workers to recruit business independently—without the need for potentially exploitative or violent third parties. In their absence, some workers were forced to go back to relying on these middlemen. Some turned to nondigital ways of recruiting customers, which leaves less room for screening.

In summer 2022, Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics (COYOTE) Rhode Island conducted a survey of sex workers and sex trafficking survivors about how the passage of FOSTA and the disappearance of Backpage had affected them. "I had to start stripping and saw customers from the strip club instead," said one respondent. "But, since it was in person I wasn't able to screen them as well so it was a lot more dangerous."

Once Backpage went down, "there was panic from everyone I knew," says Calida. "Within the first months, people still had to work but couldn't advertise or screen. They went missing. Sometimes, bodies were eventually found. Sometimes, there weren't bodies at all, and those people are still considered missing. People got abused because they couldn't screen. Got ripped off by clients."

What makes Calida especially angry is that this was so "unnecessary." Sex workers, people who have been trafficked, and activists warned about what would happen.

"Even now, despite the evidence, even with police admitting it was a catastrophe, there's still no apology. No changes. No hope."

Left with less ability to support themselves, some were forced into precarious situations, like staying with an abusive partner in order to have housing. Some had to put important goals they had been working toward on hold.

Lola Minaj, a trans sex worker, credits sex work with providing her the income "needed to afford medical/cosmetic treatments" and to become "the woman I am growing to be." But after Craigslist ditched adult ads and Backpage was seized, "the next five years were very rocky." She says she "went back to living as a boy" in order to get a job. Now, "I live as Lola again. Thank God. I have also came back to sex work," says Minaj. But "the escorting hustle sure has changed. The boards are limited. The ad spots are either phishing scams, scrapper sites, or actively working with the FBI."

'We're the Canary in the Coal Mine for the Internet'

The dearth of new possibilities for adult advertising surely stems in part from the Backpage prosecution, which showcases how far the government will go against platforms that don't shy away from such content. But it's also a function of FOSTA, which among other things makes hosting content with the intent to "promote or facilitate the prostitution of another person" a federal crime. The twin effect has been to make web platforms wary of allowing any content related to sex and sexuality at all.

"Backpage and FOSTA are inextricably linked," says Ricci Joy Levy, president and CEO of the Woodhull Freedom Foundation. "FOSTA was born of the challenge in shutting down Backpage." And why did people want to shut down Backpage? "To censor sex and sexuality," says Levy.

Over the past five years, FOSTA has succeeded in chilling online speech about sex without the necessity of anyone bringing charges or lawsuits.

"The fear of the consequences of FOSTA [has] resulted in strict censorship of images and content by social media platforms," says Levy. "In addition to what you would anticipate might be censored…any content related to sexuality is restricted on so many of the mainstream platforms. On Facebook or Instagram, you can't reference sexual pleasure…you can't sell a sex toy or sexual product…sex therapists and counselors aren't able to place ads."

Even "email services are starting to reject an email that has the word sex or sexuality in it," adds Levy, noting that her organization has had firsthand experience with this. "Words for body parts that are nonanatomically correct—like ass, boobs—they're being censored. We saw Tumblr remove all sexually oriented content, and that censored a lot of LGBTQ content."

And things are likely to get worse, as the takedown of Backpage and the passage of FOSTA prove a useful playbook for future censors.

Now, whenever people want to censor or censure something, "it's 'child endangerment,' or 'sex trafficking,'" says Larkin.

Indeed, social media giants including Twitter and Reddit have recently faced lawsuits accusing them of facilitating sex trafficking. Activists and some politicians have also been calling for the shutdown of porn websites on these grounds. And there's been ample legal controversy over what it means to "facilitate" or "promote" a crime—including, now, abortion in many states—and how this impinges on protected speech.

Levy says what we've seen with Backpage and FOSTA is "the tip of the iceberg." While they're part of a long-running "war on sex and sexuality," they can be built on "to force online platforms to censor other categories of speech," says Levy. "It could be about drugs, it already is about abortion. There are questions around terrorism. Guns."

Woodhull is one of a few groups challenging FOSTA in federal court. Levy says the challenge "is critically important, not just for sex workers or sexual expression but to hopefully preserve online freedom" in many realms.

"We're the canary in the coal mine for the internet," suggests Larkin. "It's being proven now."

As he, Lacey, and their co-defendants await an August trial, sex workers, too, are still suffering from the seizure of Backpage and from FOSTA.

"Sex workers are expected to die silently with grace every time a bad policy [gets] enacted. But I'm not graceful. And I'm not giving up," says Calida. "People should not be forced into dangerous conditions over politics and misplaced moral crusades."

Show Comments (32)